A European mission will intercept an unknown comet for the first time

The “Comet Interceptor” will launch in 2028 and loiter a million miles away until an interesting and accessible comet is found.

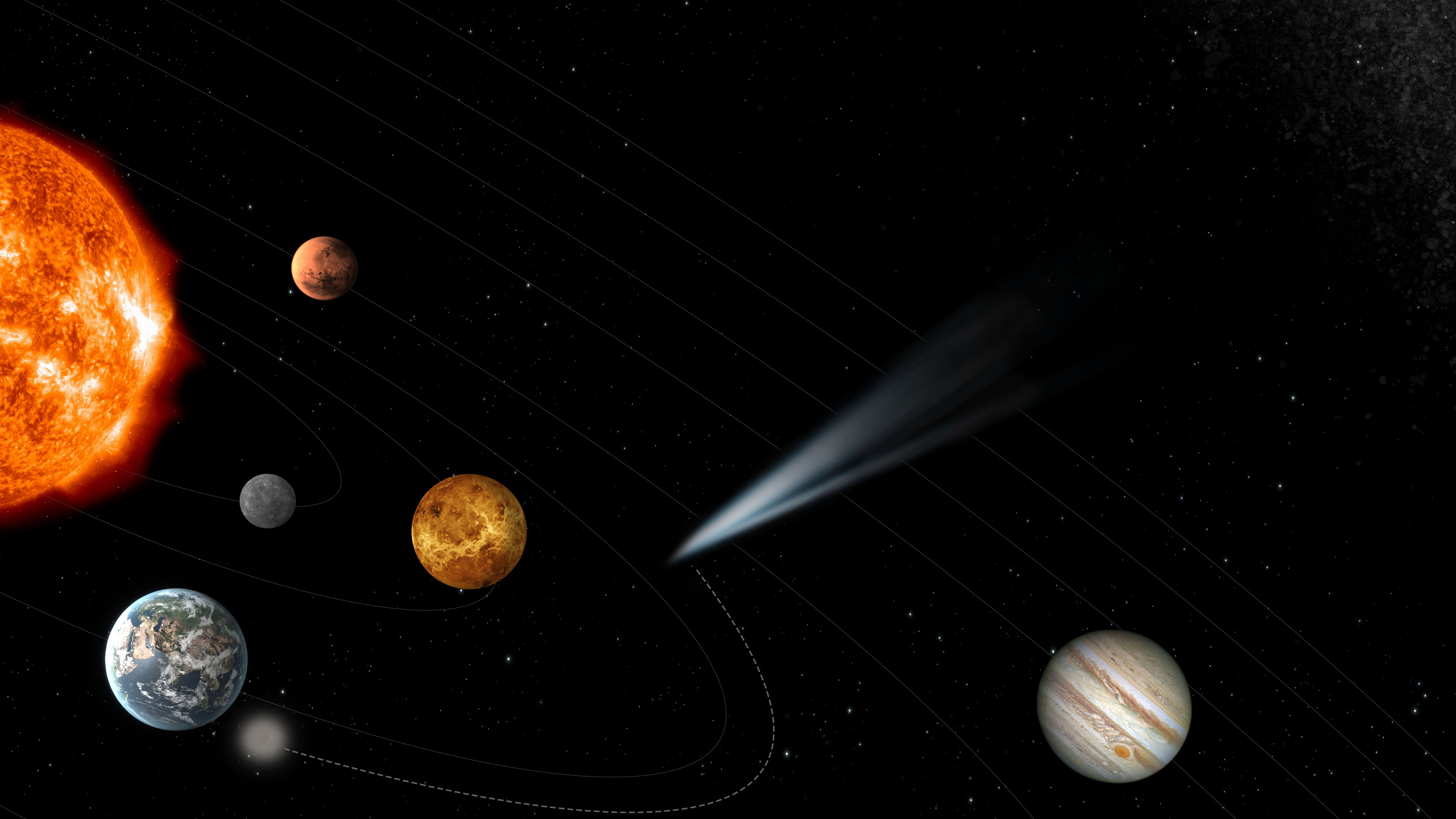

The plan: On June 19, the European Space Agency announced plans to launch a fleet of three small spacecraft to intercept a comet that will be visiting the inner solar system for the first time. Only thing is, it just doesn’t know which comet yet.

The Comet Interceptor will comprise three spacecraft that will tag along with Ariel, a larger observatory designed to study the atmospheres of planets orbiting distant stars. The Interceptor’s designers are counting on a new, giant telescope being built in the Chilean desert to find a target far enough in advance to plot an intercept course. They are hoping such a suitor will be found within two to three years of the Interceptor’s arrival at a place called L2, about a million miles from Earth (roughly four times the distance to the moon).

Action: Once a comet is detected on a suitable trajectory, the three spacecraft will leave L2 to chase their quarry across the solar system. Between one day and three weeks before rendezvous, the Interceptor will split into its three component parts.

Two of the spacecraft will pass close to the comet’s nucleus (its solid central part), where they hope to gather enough data to understand the structure of both the nucleus and the comet’s tail. One of these will be built by Japan’s space agency and the other by the European Space Agency (ESA). The third spacecraft, also built by ESA, will pass by the comet at a safe distance (between 100 and 1,000 kilometers) and act as a backup and data relay.

The precedent: Nine comets have already been visited by about a dozen different spacecraft. But all prior missions have been to comets that had already spent numerous orbits (or parts of them) in the inner solar system—not first-time interlopers from the solar system’s distant regions or even from beyond the solar system.

Why it matters: Astronomers generally agree that some of the water on Earth came from comets, but there is heated debate about just how much. Examining comets that come from the outer reaches of the solar system could help clear that up.

Want to keep up to date with space tech news? Sign up for our space newsletter, The Airlock.

Deep Dive

Space

How to safely watch and photograph the total solar eclipse

The solar eclipse this Monday, April 8, will be visible to millions. Here’s how to make the most of your experience.

How scientists are using quantum squeezing to push the limits of their sensors

Fuzziness may rule the quantum realm, but it can be manipulated to our advantage.

The race to fix space-weather forecasting before next big solar storm hits

Solar activity can knock satellites off track, raising the risk of collisions. Scientists are hoping improved atmospheric models will help.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.