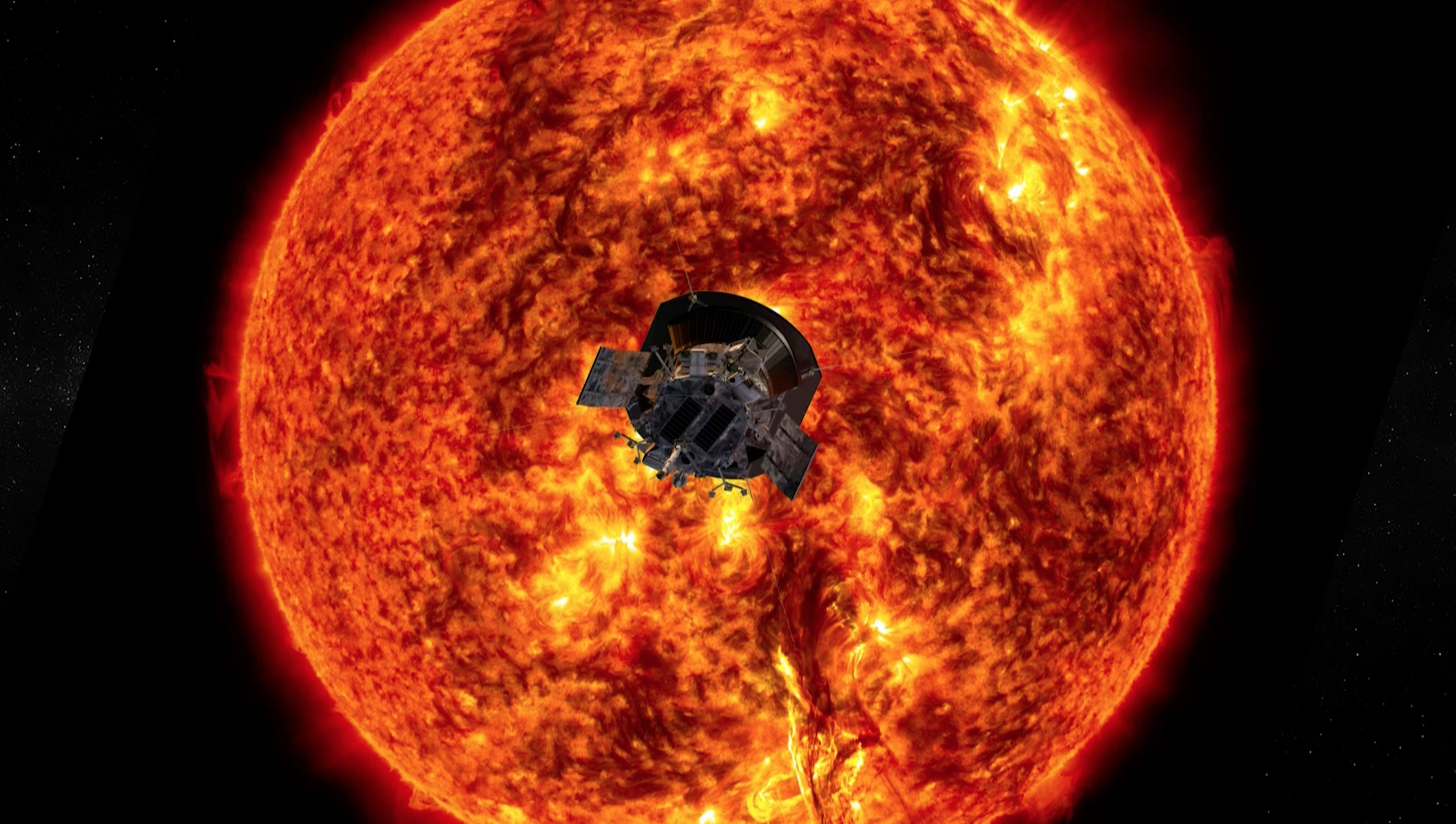

The closest ever approach to the sun has shown us the origin of solar wind

The first major results from NASA’s Parker Solar Probe are in, a little over a year after the spacecraft set the record for the closest approach to the sun by an artificial object.

Parker’s big year: Launched in August 2018, the Parker Solar Probe was built to study the sun and make the sharpest observations of the corona (the wreath of ultra-hot plasma that surrounds it). In October 2018, the probe came within 26.55 million miles (42.3 million kilometers)of the sun, surpassing the record set by the Helios 2 spacecraft in 1976.

The mission’s first results: The findings from that 2018 approach, published Wednesday in four new papers in Nature, suggest that solar wind and the sun’s magnetic field both originate from cool holes in the corona, where temperatures are 1.1 million °C (2 million °F).

The solar wind is a stream of charged particles belched out by the corona. The studies reveal that reversals in the sun’s magnetic field lines are responsible for accelerating this wind away from the sun. As the wind’s particles stream out of the cooler coronal holes, they move along the magnetic field lines. These lines will sometimes do a 180-degree flip, only to flip back to their original orientation anywhere from a few seconds to several hours later. These flips release lots of energy that acts upon the solar wind, sending it out into the solar system. Scientists are not yet able to explain what’s causing these flips, although they may have something to do with plasma jets that sometimes explode off the surface of the sun.

Why it matters: Solar wind has the potential to severely damage Earth’s electrical grids or other telecommunications equipment. Although the Earth’s own magnetic fields provide an excellent barrier against most solar wind, huge events could very easily knock out much of our infrastructure. Scientists hope that by learning more about the origin and behavior of solar wind, we can develop early warning systems for solar storms and figure out better strategies to guard against them.

What’s next: The Parker Solar Probe is far from finished. By 2025, it should get to within 3.9 million miles of sun's surface, facing temperatures of up to 1 370 °C and traveling as fast 430,000 miles per hour.

Update: We have corrected an error in the final section

Deep Dive

Space

How to safely watch and photograph the total solar eclipse

The solar eclipse this Monday, April 8, will be visible to millions. Here’s how to make the most of your experience.

How scientists are using quantum squeezing to push the limits of their sensors

Fuzziness may rule the quantum realm, but it can be manipulated to our advantage.

The race to fix space-weather forecasting before next big solar storm hits

Solar activity can knock satellites off track, raising the risk of collisions. Scientists are hoping improved atmospheric models will help.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.