A New Chip to Bring 3-D Gesture Control to Smartphones

The clickwheel of the first iPod worked by measuring electric field disturbances in one dimension. The first iPhone touch screen functioned similarly, but in two dimensions.

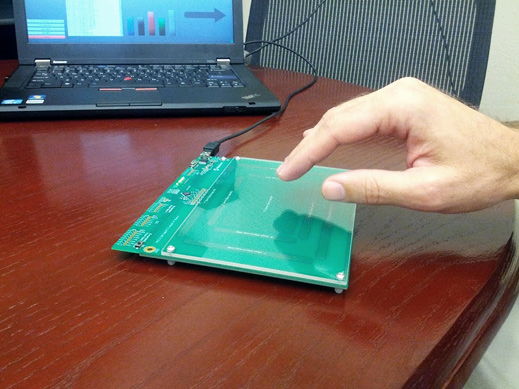

This week, Microchip Technology, a large U.S. semiconductor manufacturer, says it is releasing the first controller that uses electrical fields to make 3-D measurements.

The low-power chip makes it possible to interact with mobile devices and a host of other consumer electronics using hand gesture recognition, which today is usually accomplished with camera-based sensors. A key limitation is that it only recognizes motions, such as a hand flick or circular movement, within a six-inch range.

“That’s the biggest drawback,” says University of Washington computing interface researcher Sidhant Gupta. “But I think, still, it’s a pretty big win, especially when compared to a camera system. It’s low-cost and low-power. I can completely see it going into phones.”

Gesture recognition technology has advanced in recent years with efforts to create more-natural user interfaces that go beyond touch screens, keyboards, and mouses (see “What Comes After the Touchscreen?”). Microsoft’s Kinect made 3-D gesture recognition popular for game consoles, for example. But while creative uses of the Kinect have proliferated, the concept hasn’t become mainstream in desktops, laptops, or mobile devices quite yet.

Today, Microsoft, along with other companies such as Leap Motion and Flutter, are working to improve upon and expand camera-based technology to new markets (see “Leap 3D Out-Kinects Kinect” and “Hold Your Hand Up to Play Some Music”). For smart phones and tablets, Qualcomm’s newest Snapdragon mobile device chip includes gesture recognition abilities, via its camera, but few mobile devices make use of gesture control.

Despite the six-inch distance limitation, the electrical-field controller could have some interesting advantages compared to camera sensors. “It’s really complementary,” says Fanie Duvenhage, director of Microchip Technology’s human-machine interface division.

Power consumption is a key issue for battery-powered devices. Microchip’s controller uses 90 percent less than camera-based gesture systems, the company says, and it can be left always on, so that it could be used to, say, wake up a smart-phone screen from sleep mode when a person’s hand nears.

The controller works by transmitting an electrical signal and then calculating the three-coordinate position of a hand based on the disturbances to the field the hand creates. Whereas many camera systems have “blind spots” for close-up hand gestures and can fail in low light, the Microchip controller works well under these conditions and doesn’t require an external sensor (its sensing electrodes can sit behind a device’s housing).

Perhaps most interesting, the controller could easily go into electronics that don’t have a camera, including car dashboards, keyboards, light switches, or a music docking station. In fact, Microchip Technology already sells components to 70,000 customers that make these products. Duvenhage says he imagines interesting uses in cars, such as controlling an in-car navigation system, or in medical or kitchen settings where users might not want to touch a button or screen.

The controller comes with the ability to recognize 10 predefined gestures, including wake-up on approach, position tracking, and various hand flicks, but it can also be programmed to respond to custom movements. Similar to the programming of voice recognition software, Microchip Technology built the gesture library using algorithms that learned from how different people make the same movements. These gestures can then be translated to functions on a device, such as on/off, open application, point, click, zoom, or scroll.

The precision is about the same as using a mouse, but the system has limitations. It can’t yet distinguish between, say, an open hand and a closed fist, or simultaneous movements of different fingers, an area the company wants to improve.

Today, less than a year after acquiring the German startup that developed the technology, the company is making a development kit available for sale, and Duvenhage says they’ll be looking to customers to see what uses they create. Microchip plans to reach mass production levels by next April, and it expects to see the first products using the technology on the market sometime next year.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.