Why Microsoft’s Next CEO Should Break Up the Company

Microsoft missed a golden opportunity when it settled its anti-trust case with the U.S. Department of Justice on November 2, 2001. The government had proved in court that Microsoft was a monopoly and had illegally “tied” the distribution of its Web browser Internet Explorer to Windows, but the court’s chosen remedy—breaking Microsoft into two companies—was thrown out on appeal.

It turned out the trial judge had given secret interviews to the media and publicly disparaged Microsoft officials outside the courtroom. And by then, the Bush administration had taken office and was not interested in breaking up a major U.S. corporation. Then the 9/11 attacks gave us new enemies to worry about. Microsoft got off with a slap on the wrist.

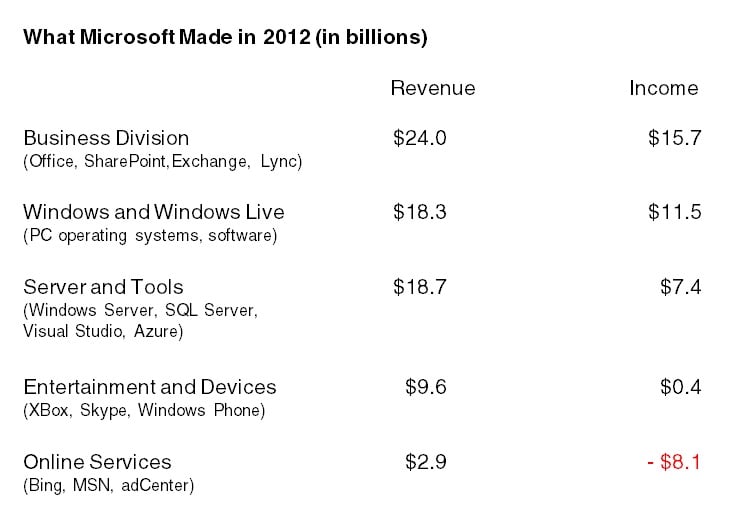

Today’s Microsoft is a behemoth. Apple may be making more money, but Microsoft is doing more things—from writing operating systems and applications, creating software for corporate servers, running cloud-based services for customers, developing hardware, and sinking billions a year into a still unprofitable Online Services Division, which runs the Bing search engine.

Having built Microsoft into a company that makes the vast majority of its income from catering to business customers, CEO Steve Ballmer announced last week that he is ending his 13-year run as Microsoft’s CEO.

The next CEO should break up the company.

The reasons are quite different from those that led to the U.S. case against Microsoft. That case revolved around the question of whether or not Microsoft could force customers purchasing its Windows operating system to also take a free copy of its Internet Explorer browser. Microsoft insisted the browser was part of the operating system. The government said the browser was independent and selling them together was an anti-competitive practice called “tying.”

What made Microsoft the giant it is wasn’t this tie-in, though. It was more like “lock-in.” Even when the case was being litigated, it was clear that the real source of Microsoft’s monopolistic power was the link between the company’s desktop operating system (Windows), its word processor, spreadsheet and presentation programs (Office), its corporate e-mail and calendar (Exchange), developer tools (Visual Studio), and many other applications

This suite of great programs worked best together, creating a kind of Venus flytrap effect for corporations and governments that fully committed to running Windows everywhere. Microsoft collected billions. By 2003, it had accumulated a $43.4 billion cash surplus. Today it has $77 billion.

But Microsoft also got locked-in—to the easy money that comes from satisfying a captive customer base. The company that had made its fortune by riding the disruptive technology of the personal computer became so focused on keeping those revenues coming in that it stopped being able to execute on the next big thing. Case in point: since Ballmer took over, the number of Internet users relying on Internet Explorer dropped from a high of more than 85 percent to roughly 12 percent today (53 percent use Google’s Chrome and 29 percent use Mozilla’s Firefox).

Microsoft has earned a reputation of hiring some of the brightest people in the industry—but when those people develop breakthrough technology, those products frequently have to be killed so that they do not threaten the company’s cash cows.

One example is Courier, a clever two-screen tablet that 130 Microsoft employees developed between 2008 and 2010. Unlike Apple’s iPad, which is designed for consuming content, Courier was designed for creating it. The tablet would have launched around the same time as the iPad and might have fundamentally changed the way tablet computing evolved, but Microsoft killed the Courier because it was perceived as a threat to some future version of Windows. (Jay Greene wrote a revealing article explaining why Courier was killed, including photos of the tablet and its screens, back in 2011.)

While some Ballmer postmortems pin Microsoft’s downfall to the company’s inability to make that shift to mobile devices, the problems are deeper than that. Kurt Eichenwald’s August 2012 article in Vanity Fair, “Microsoft’s Lost Decade,” places the blame on internal conflicts and bureaucratic paralysis. Microsoft didn’t need innovation so much as a workforce of interchangeable programmers that could fix bugs, address security concerns, respond to customer requests, and bring out a new set of operating systems and applications releases every two or three years in order to force its customers to shell out more cash for upgrades.

To really innovate again, the next CEO of Microsoft should break up the company into parts (what some are calling “Mini Bills”). Here’s my prescription for a few of them:

An operating systems company. It would run Windows and capitalize on the huge ecology of business applications that’s built up around it. For a change, though, this company would open-source the operating system, creating a new version of Open Source Windows that is small, easy to maintain, efficient, and highly securable. Such a system would put Linux on the defensive. The company would derive its revenue from service, support, and consulting.

A desktop applications company, which would maintain and improve those apps that customers around the world rely upon. These apps, like Word, would remain closed source, but they would become operating system agnostic—running equally well on Windows, Mac, Linux, and in the cloud.

A server applications company. This company would be the closest to the Microsoft of today. Maybe it could even keep the name. It would continue to cater to Microsoft’s demanding business customers.

An entertainment spin-off. This one gets XBox, Microsoft’s hardware engineers, and the game designers. What their future holds here is anybody’s guess. Despite huge customer visibility, the annual report makes it clear that this division just isn’t all that profitable.

Finally, Microsoft’s online division will be forced to swim or sink. Microsoft has already realized that it never had any business running a travel agency (Expedia) or a cable news network (MSNBC). It probably doesn’t need to be running a search engine or a consumer e-mail provider either.

Ballmer is leaving a Microsoft that has become a mass of infighting and tangled management. The antidote is simplification, and the only way to achieve that is through radical restructuring.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.