Headed to Mars? Gas Up Near the Moon.

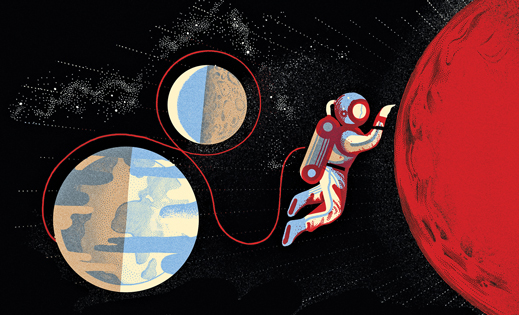

Launching humans to Mars may not require starting out with a full tank of gas: a new MIT study suggests that a Martian mission could lighten its load considerably by refueling near the moon.

Previous studies have suggested that lunar soil and water ice in certain craters of the moon could be mined and converted to fuel. Assuming that such technologies are established by the time of a mission to Mars, the MIT group has found, a Mars-bound spacecraft could reduce its mass upon launch by 68 percent if it reduced its initial stores of fuel in favor of making a pit stop near the moon for more.

The team proposes that missions beyond Mars, too, may benefit from a supply strategy that hinges on “in situ resource utilization”—producing and collecting resources such as fuel, and provisions such as water and oxygen, along the route of space exploration.

“There’s a pretty high degree of confidence that these resources are available,” says Olivier de Weck, SM ’99, PhD ’01, a professor of aeronautics and astronautics and of engineering systems at MIT. “Assuming you can extract these resources, what do you do with it? Almost nobody has looked at that question.”

Postdoc Takuto Ishimatsu developed a network flow model to explore the movement of cargo and commodities, such as fuel, in a supply-chain network in space. The model assumes a future scenario in which fuel can be processed on the moon and transported from there to rendezvous points in space. Likewise, the model assumes that fuel depots can be located at certain Lagrange points—locations in space where objects may remain stationary, caught between the gravitational fields of Earth and the moon.

Ishimatsu found the most mass-efficient path involves launching a crew from Earth with just enough fuel to get into orbit around the planet. A fuel-producing plant on the surface of the moon would then launch fuel tankers into space, where they would enter gravitational orbit. The tankers would eventually be picked up by the crew, which would head to a nearby fueling station to gas up before heading to Mars.

“Our ultimate goal is to colonize Mars and to establish a permanent, self-sustainable human presence there,” Ishimatsu says. “However, equally importantly, I believe that we need to ‘pave a road’ in space so that we can travel between planetary bodies in an affordable way.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.