Inside the First VR Theme Park

I’m standing on a dark platform at the edge of a maze of gray walls, where two guides are helping me into my gear. They place a bulky helmet crammed with a virtual-reality headset, headphones, and gesture-recognition hardware on my head, and help me strap a modified laptop to my back.

The guides step away. I stare through my headset at a blue-lined digital abyss. Suddenly, the endless space in front of me opens up with a virtual sizzle of electricity, revealing the entrance to an ancient temple, hidden deep in a lush jungle, where ancient carvings and forgotten treasures await my inspection.

Hesitantly, I step forward, curious to explore but unsure of what will happen. I reach out to touch one of the crumbling stone walls on my left, and while it doesn’t feel quite the way it looks, it’s there, which is reassuring. There appears to be a glowing torch on the wall; I reach out and feel something that could indeed be a torch, so I pick it up and use it to light my way as I wander down the dark passageways, inspecting carvings and statuary along the sides.

Occasionally, I run my free hand over a wall or a fallen stone, just to get a reality check; yep, still there. A fire burns in the middle of one passageway, and I actually feel its warmth on my face. At one point, standing in a cave on a rickety-looking platform overlooking an underground pool, I press my hand onto a small podium in front of me, and the platform rumbles and rises off the ground. Eventually, I spy a room full of glowing treasure ahead of me, but annoyingly, a virtual earthquake makes the distance impassible before I can snag any of it.

I’m entranced, and the dozen pounds of electronics weighing me down seem to melt away.

I’m exploring the Void, a new entertainment center being built in the suburbs of Salt Lake City. It combines virtual reality with elements of the real world, like walls, wind, and sprays of water. You walk around and touch things that match up with any number of fantastical worlds you see through a VR headset.

There’s a lot going on in virtual reality these days, much of it touched off by Facebook’s decision to purchase headset maker Oculus for $2 billion in 2014. Oculus’s first consumer headset, the Rift, finally comes out this winter. In the meantime, Google and Samsung have released devices that let you look into virtual worlds on your smartphone.

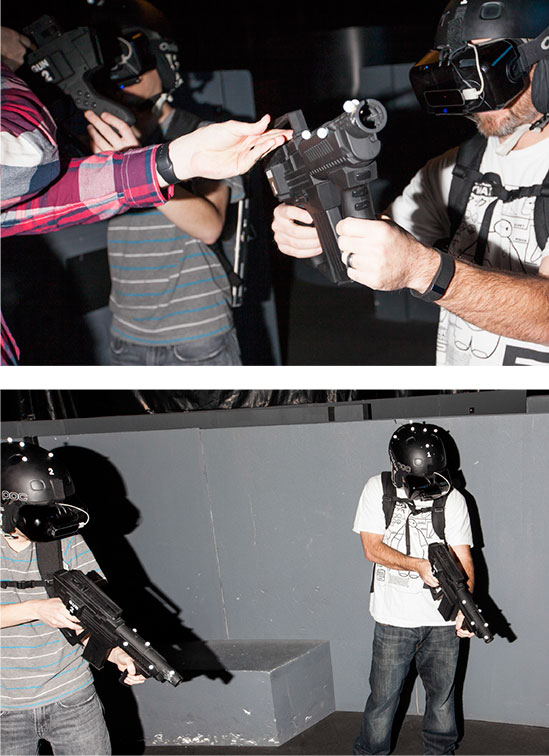

Bottom: Walls on the Void’s beta stage are arranged so that they can be used for a wide range of experiences, like navigating a decrepit temple or a futuristic research facility.

But even if those devices bring a whole new kind of entertainment to your living room, the creators of the Void are thinking bigger. Led by Ken Bretschneider, a tech entrepreneur who previously created the Internet security company DigiCert, the company is building an eight-acre gaming center in Pleasant Grove, Utah, possibly the first of several around the country. Groups of six to eight headset-clad visitors will pay $34 apiece to explore virtual reality together for 20 minutes at a time, roving 60-by-60-foot stages filled with dense foam walls, replete with effects like water and wind.

Though the full-size version of the Void isn’t slated to open until August or September, the company is already selling out time slots at a beta center connected to its office in neighboring Lindon. There, curious visitors pay $10 apiece to try out the first interactive experiences, which at this point span just six or seven minutes and are set on a stage that’s just 30 by 30 feet.

That’s where I am. And while it is just a quarter the size of stages that are planned, it’s still more than large enough for me to feel captivated (and a bit spooked) while walking through the ancient temple and, later, a dingy futuristic research facility where I have to shoot giant spiders and an alien.

Think of it as the rainy-Saturday laser tag of the future, but on steroids. Lots of steroids.

“Laser tag is just what it is—it’s taking guns and going shooting at each other inside a designed environment and trying to score points,” Bretschneider says, slouching in his company-branded T-shirt, black jacket, and black jeans in the Void’s cramped conference room. “The Void is so much more than that.”

Virtual bullets

Bretschneider has long been a fan of the kind of fantasy and make-believe that are key to the Void. He’s popular in his Salt Lake suburb for turning his home into an over-the-top haunted house on Halloween. And before focusing all his attention on the Void he was actually building something much larger: an ambitious theme park called Evermore, with a sort of Victorian steampunk vibe.

Bretschneider got started on Evermore in 2012—the same year DigiCert was sold—and purchased 40 acres of land in Pleasant Grove to house it; a team of workers was tasked with making statues and buying props for the site. But by 2014, he had already plowed about $14 million of his own money into the park and figured completing it would cost $350 million to $400 million, which he couldn’t finance on his own.

Right: A scene of what you see inside one of the Void experiences.

So the people working on Evermore decided to switch focus. They were already planning to include an attraction that mixed virtual worlds and reality. What if they just concentrated on that and scrapped the rest of the park?

The first prototype system for the Void cost Bretschneider about $250,000. Built in late 2014, it consisted chiefly of an Oculus developer headset and some electromagnetic tracking devices to monitor the user’s position in virtual space. A 10-foot-long plywood wall served as the physical environment, and it was paired with a virtual-reality view of a spaceship’s hallway on the headset. “It was enough to convince us that we wanted to take it and really run with it,” Bretschneider says.

Since then, the team behind the Void has made a lot of progress. It’s working with a product design company to make its own technology for navigating this weird meshed world—such as a proprietary headset that the company claims has a wider field of view than Oculus’s and a vest with haptic feedback to simulate sensations like getting shot by virtual bullets. The vest will include a hefty computer and battery, too, for making everything work without tethering you to a desktop computer. The Void is also building a radio-frequency system for positional and body tracking.

The special equipment isn’t ready yet, so for now, the Void is hacking together a variety of available gadgets: things like Beats headphones, an Oculus DK2 headset, a laptop, and a Leap Motion controller. Still, even this gear worked impressively well when I tried it in November.

Bottom: In the Void’s Research Facility, players have to shoot giant spiders and an alien trapped in an observation tank.

This was evident when I stepped into the lost-temple world of Dimension One: the world around me looked crisp and properly proportioned. The virtual features of the temple—a bench, a wall, a ledge—nearly always matched up with what I expected when I reached out to touch them.

It was also simple to figure out what I needed to do in the Void. In that temple, for instance, I just had to follow some audio instructions and wander around. Nobody wants to shell out the price of two movie tickets for a 20-minute experience and then feel paralyzed and uncertain.

Building the Void is not simple, though. The stage was constructed with a curved hall around the edge, which can be used for a VR technique called redirected walking—essentially making you feel as if you’re walking in straight line even if you’re looping around a given space. This, plus some strategic twists and turns with the maze-like walls on the stage, can bring you back to the same hall over and over, though with changes to the virtual visuals in your headset, you’ll feel as though you’d never been there before.

After traipsing through the ancient temple, I tried out a first-person-shooter game called Research Facility. For that, I had to hold a big prop gun the whole time, shooting gross mutant spiders as I made my way through a research center in search of an alien. It felt nothing like Dimension One, and yet I was traversing the same general space.

Other tricks help, too. That elevator I rode during my temple exploration? It was actually a small podium attached to a chain contraption that, when I pressed my hand on it, moved down toward the ground while transducers in the surface beneath my feet made the platform seem to rumble. Visuals on the headset showed the water down below getting farther and farther away. The Void uses plenty of simple effects, too, like a fan blowing wind in my face and nozzles spritzing me with mist to make me feel I was really standing on the edge of a lush jungle, a waterfall gushing in the distance.

Complicated or not, the cumulative effect was dazzling. It felt longer than 15 or 20 minutes, which is an effect Bretschneider is banking on: “It’s so immersive, and there’s so much that you’re experiencing, that it’s almost like 20 solid minutes of that experience is getting very equivalent to just watching a film.”

VR’s second chance

Scott Smith, an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina who studies hotels, resorts, and theme parks, has seen something like the Void. It was way back in 1992 at a shopping mall, and the technology didn’t work very well. Yet while the concept isn’t entirely new, virtual-reality technology has changed substantially since then, and consumer expectations have, too.

People want to interact with their entertainment rather than just acting as spectators, he says. He points to the popular Buzz Lightyear’s Space Ranger Spin ride at Walt Disney World in Florida as proof—on that attraction, people sit in cars equipped with laser guns meant for firing. “This is what today’s guests want,” he says. “They don’t want to watch the movie; they want to be in the movie.”

Still, he thinks the Void’s success won’t hinge just on making its technology feel interactive. It will also need to give visitors goals to work toward, rather than just handing them guns and commanding them to kill virtual zombies, he says. “You need zombies rushing at you to get your heart going, but you also want a story line behind it—you’re on a quest or you have to solve riddles, be a problem solver, use your brain a little bit.”

The Void plans to offer a variety of experiences visitors can choose from. Some are being developed in house; a video-game company and researchers at the University of Utah are working on others. A local Mormon organization, I’m told, is developing a way for people to feel as if they’re walking through historic Jerusalem.

Whatever the content is, Bretschneider says it will change quarterly. “I can take you into a multiplayer game scenario and you can play that way, but I can also take you into an educational adventure. I can take you into a puzzle-solving adventure. I can have you live a film. I can take you into a museum of the future,” he says. “There are really no limitations.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.