Fitbit CEO on Wearable Gadgets, the Future of Sensors, and Wall Street

In the six years since Fitbit began selling its first fitness tracker, a $100 clip-on device that used a growing flower on its tiny display to indicate how active you’d been, the market for wearable gadgets has changed tremendously.

Companies large and small have flooded the market with all kinds of fitness trackers, smart watches, and other wearable devices. According to technology market researcher IDC, between July and September of 2015, 21 million wearables were shipped out, about triple the number from a year earlier.

And while Fitbit is still the leader, commanding 22 percent of that market, its slice of the pie is much slimmer than the nearly 33 percent it had a year earlier. Apple, meanwhile, which started selling the Apple Watch last April, has carved out close to 19 percent of the market, taking the number-two spot.

At CES in Las Vegas this week, Fitbit seemed to indicate that it’s feeling the heat of this increasing competition, as it unveiled a $199 fitness-geared smart watch with a color touch screen called Fitbit Blaze that looks like its answer to the Apple Watch. Investors were underwhelmed, as shares of Fitbit fell 18 percent following the announcement. They fell further after news that a class action lawsuit had been filed against the company alleging inaccurate heart rate information on two of its trackers (in a statement, Fitbit said it doesn’t believe the case has merit).

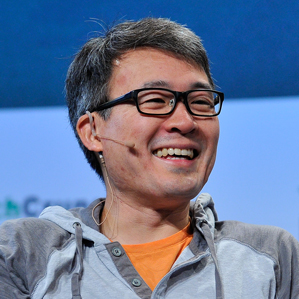

In a conversation with MIT Technology Review, Fitbit CEO and cofounder James Park said he doesn’t worry about the stock price and that “the Wall Street investor and our customers are not necessarily the same type of people.” He also talked about how the wearable gadget market is changing and what he hopes the company’s devices will be able to do in the future.

How do you see the capabilities of wearables evolving as more companies start making them and the components that go into them become smaller and cheaper?

A big theme for us is going to be the inclusion of more advanced sensors. So you can envision in the future what really we want to do is get to the point where not only are we addressing lifestyle conditions but more chronic conditions as well, whether it’s heart disease, obesity, etc.

What kinds of sensors and tracking capabilities are you hoping to add to future devices? Fitbit already uses sensors to track things like activity and heart rate, but your products don’t yet include sensors that can do things like measure stress.

I can’t talk specifically about the exact things we’re working on but I think broadly as an industry, definitely consumers are interested in tracking deeper metrics about their sleep, if we think about sleep phases or even being able to diagnose and address sleep apnea—those are big issues. Right now, to really diagnose sleep apnea, you have to go to a sleep lab, which is pretty expensive and impractical for a lot of people because you have to spend a night there.

And then secondly think about issues like blood pressure, stress—those are all different types of metrics that consumers are going to be interested in that could be addressed with future sensors.

The Fitbit Blaze seems like a clear response to the Apple Watch. Was this intentional, and how did you try to differentiate from Apple’s offering?

Blaze has been in development for quite a while. For us it’s one part of a pretty comprehensive lineup; health and fitness devices that people can pick and choose from, because there’s no one-size-fits-all. We’re trying to give people a lot of different options.

I said this in our press conference: it may look like a smart watch but honestly I don’t think smart watches have really taken the world by storm. So what we do is we look at what our consumers need.

One, Blaze is fitness-focused, so most of the features are optimized for an active fitness user. Secondly, a lot of the things that are in smart watches I think really overwhelm people. We made trade-offs to include the right set of functionality and what we gained is something our users really appreciate, which is battery life. Blaze has five days of battery life.

Clearly, you didn’t want to pack too many features in to the Blaze—it does just a handful of things beyond fitness tracking and guiding you through workouts, like letting you receive text messages and call and calendar alerts, and it doesn’t work with any third-party apps. Could apps come in eventually?

Definitely the hardware’s there to support it, but we want to be pretty selective about making sure it’s not an overwhelming experience for users.

Over time, will the fitness tracker remain a stand-alone device that I strap to my wrist or clip to my pocket? It seems likely it could just become a feature of a more full-featured wearable, like a smart watch.

I would say if you look at people’s wrists, most people don’t wear watches, in general, and in particular smart watches. It’s all about giving people different choices for how they want this data to be tracked. There’s not going to be one particular form factor that everyone’s going to wear. It’s going to be a very personal choice.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.