Glaxo and Verily Join Forces to Treat Disease By Hacking Your Nervous System

GlaxoSmithKline and Google’s life sciences spin-off, Verily, are jointly funding a new venture that will investigate how tiny bioelectronic devices can be used to modify nerve signals and treat chronic diseases.

The pair are investing $715 million over the next seven years to fund the company, which will be known as Galvani Bioelectronics. (Luigi Galvani discovered what he called “animal electricity” in 1780.) With research centers in San Francisco and GSK’s bioscience hub in the U.K., the new company will investigate how to create small, implantable electronic systems that can be used to correct irregular nerve impulses.

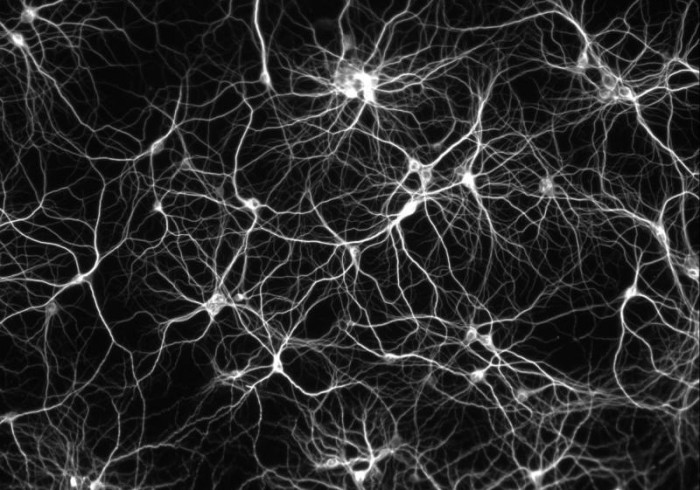

The devices—sometimes referred to as electroceuticals—place a small sheath around a bundle of nerves. There, a miniature piece of hardware can be used to block or alter signals passing through the nerve fibers. That ability makes it possible to override or augment signals from the brain in order to control the organs at the end of the nerve to treat disease.

Kris Famm, GSK's head of bioelectronics research and the new president of Galvani Bioelectronics, told Reuters that the first such devices may be the size of a pill, while later iterations could be as small as a grain of rice. The company’s goal is to ready its first devices for regulatory approval within the seven years of funding.

Currently, however, there are no specific product plans for Galvani Bioelectronics. A spokesperson from GSK told MIT Technology Review that the company will look to “tackle a wide range of chronic diseases that are inflammatory, metabolic and endocrine disorders, which includes Type 2 diabetes, but nothing more specific yet.”

GSK already has experience in the area of electroceuticals. Moncef Slaoui, chairman of vaccines at GSK and the chair of the new company’s board, publicly acknowledged GSK’s involvement in the field in a 2013 Nature paper. It now funds as many as 80 external researchers working in the area, according to Bloomberg. Verily is a newcomer to electrified medicine, but has been ambitious in its other ventures, which include embeddable glucose sensors and an electronic contact lens for diabetes patients.

All that said, Galvani Bioelectronics is working in a relatively young field that Slaoui himself only became convinced by in 2012. In a New York Times article, he explained that his initial reaction to the suggestion that the nervous system could be hacked to treat disease was one of suspicion. “C’mon? You’re gonna give a shock and it changes the immune system? I was very skeptical,” he explained.

Clearly, both Verily and GSK have been won over by the approach. Now Galvani Bioelectronics just has to show that their confidence is well-placed.

(Read more: Reuters, Bloomberg, Endpoints, “Alphabet Reveals the Growing Cost of Its Moon Shots”)

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.