Melting Down, Building Up

I spent my teens reading about p-set sunrises and grand academic adventures on the MIT Admissions blogs, scouring Popular Science and Technology Review for news of the scientific and technological progress that served as their backdrop. At my MIT interview seven years ago, I said I wanted, like the students and scientists I’d read about, to be broken down and rebuilt. And that’s exactly what happened in my time at MIT.

I documented the breaking in a 2012 blog post for MIT Admissions, titled “Meltdown,” which I wrote from a low point that many MIT students have experienced: I was missing sleep and class to catch up on p-sets and falling further behind, not calling home, not hanging out with friends, not thinking past the next deadline. I worked alone in my dorm’s basement, watching the feet outside through the tiny window above the piano I’d forgotten how to play. But when “Meltdown” went viral, the outpouring of support at MIT and beyond made me feel far from isolated, and the post was followed by campus-wide introspection on MIT culture and student stress.

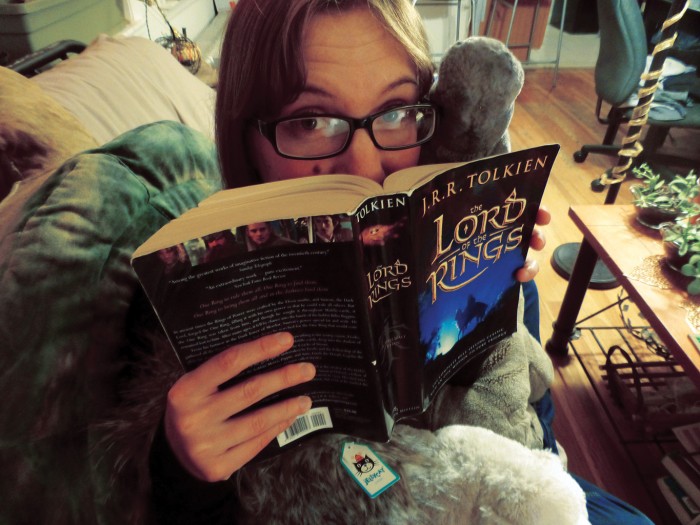

Another Admissions blogger, Anna Ho ’14, wrote about stripping away non-work activities and putting back the ones you aren’t you without. I think that is what it means to melt down and build back up: you gain a deeper understanding of what you care about and a deeper appreciation for the happiness it brings you. Rebuilding, for me, was making space for the things that have always made me me—calling and visiting my family, cooking and eating with people I care about, playing piano and reading, and taking long evening walks watching the warm lights of Cambridge come on after sunset.

After “Meltdown,” I learned to view health and education as common goals that I, my mentors, and my peers were all working toward together. It’s hard to disentangle my growth from MIT’s, but I think the key to both was decreased emphasis on being hardcore, more emphasis on lifting each other up; less elevation of lonely suffering, more encouragement to reach out to others. Life still felt like a battle, but it wasn’t a lonely fight. Classes seem to have gotten even more collaborative since my freshman year, with more opportunities for teamwork and peer teaching. And there is far less stigma around asking for help, both academically and medically.

I’ve learned to give myself time. I’ve gotten better at respecting that I need to sleep and eat and de-stress, and I’m better able to embrace the windingness of my life path and, sometimes, a slower pace. I try to avoid measuring myself in numbers or comparing myself with my peers. Instead, I try to measure time in walks taken, pages read, and songs learned. Though it is hard to hit pause, I try to remember that sometimes it is most productive to go home or do something different for an evening—or even a few months.

I think that thriving through delayed gratification, especially at MIT or in academia generally, requires seeing ourselves as more than our progress through a traditional technical career. For some of my friends, that has meant applying MIT-style problem solving to careers in education, journalism, and science video writing. My decision to include art and writing in my career grew out of Random Hall’s decision to let students to paint on its walls. Painting got me through things that were hard to put into words. I painted tiny melting cows bubbling over a radiator on the third floor (my grandfather’s cancer), tiny cows sucked into black holes (vortices of unabating work), tiny cows hiking up mountains, flying, and exploring—always open to adventure, despite the inherent dangers.

My own adventures were possible because MIT gave me a safe place to fail. In my time at MIT, I failed a lot, I got back up a lot, and I built a career out of second, third, and fourth chances. At graduation last June, the cranes hovering over the Great Dome seemed absurdly apposite—MIT was under construction, and so was I. MIT taught me that real progress plods to the rhythm of failures and growth, melting and rebuilding. Rebuilding is a never-ending, conscious process, and MIT gave me, forever, solid bedrock to build on.

Lydia Krasilnikova ’14, MEng ’16, studied computational biology at MIT. She currently works across the street at the Broad Institute.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.