A Drug Treatment for Hearing Loss

Within the inner ear, thousands of hair cells detect sound waves and translate them into nerve signals that allow us to hear speech, music, and other everyday sounds. Damage to these cells is one of the leading causes of hearing loss, which affects 48 million Americans.

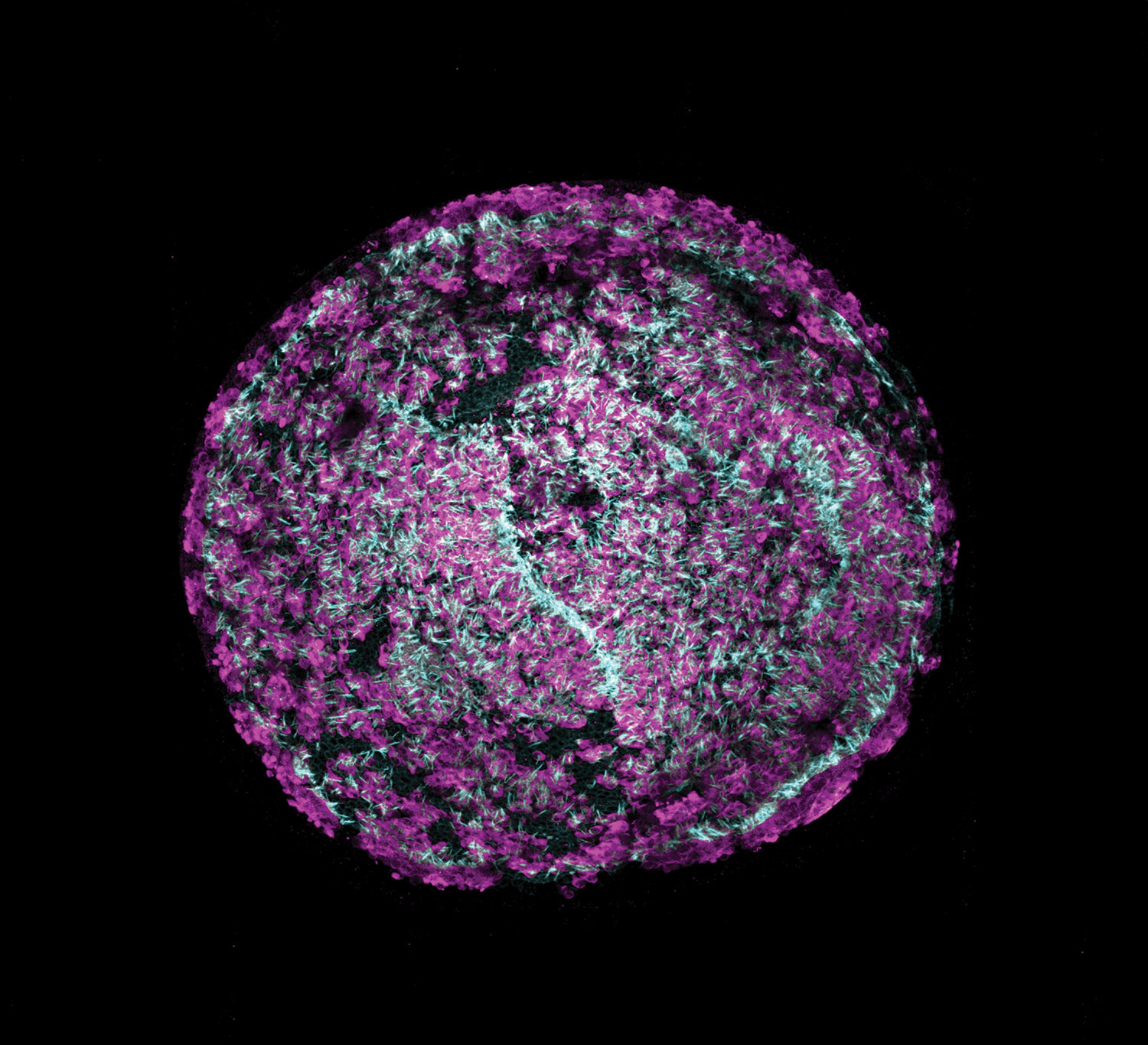

Each of us is born with about 15,000 hair cells per ear, but noise exposure, aging, and some antibiotics can cause them fatal harm. Humans, unlike some other animals, don’t regenerate the cells when that happens. However, the inner ear does contain progenitor cells that can be induced to multiply and turn into hair cells with a certain combination of drugs, according to researchers at MIT, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), and Massachusetts Eye and Ear.

“Hearing loss is a real problem as people get older. It’s very much of an unmet need, and this is an entirely new approach,” says Institute Professor Robert Langer, a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and one of the senior authors of the study, which appeared in Cell Reports.

To explore possible regeneration techniques, Langer worked with Jeffrey Karp, an associate professor of medicine at BWH and Harvard Medical School, and Albert Edge, a Harvard professor of otolaryngology based at Massachusetts Eye and Ear.

The researchers exposed progenitor cells from a mouse cochlea, grown in a lab dish, to molecules that stimulate a cell signaling pathway known as Wnt, which makes the cells multiply rapidly. At the same time, to prevent the cells from differentiating too soon, the researchers exposed the cells to molecules that activate another signaling pathway, known as Notch. Their technique led to 2,000 times more hair cell progenitors than previous approaches.

Inspired by creatures in nature that exhibit tissue regeneration, the team looked to the highly regenerative mammalian intestine, which turns over every four to five days. “We uncovered a small-molecule approach to control this process and found it worked for many tissues, including the inner ear, to produce large populations of functional sensory hair cells,” says Karp.

Some of the researchers have started a company called Frequency Therapeutics, which has licensed the MIT/BWH technology and plans to begin testing it in human patients within 18 months.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.