China Genomics Giant Drops Plans for Gene-Edited Pets

China’s largest genomics company is going public. But hold the bacon.

Starting this week, investors should be able to buy shares in BGI, China’s largest genomics company, as it completes a $251 million initial public offering. But if you were hoping to get your hands on a $1,400 pint-size pig created with gene editing, you’ll have to wait. Perhaps indefinitely.

BGI made headlines around the world in September 2015 when employees said at the Shenzhen International Biotech Leaders Summit that they intended to sell half-sized Bama pigs and inaugurate a market for gene-edited pets available in custom colors and sizes.

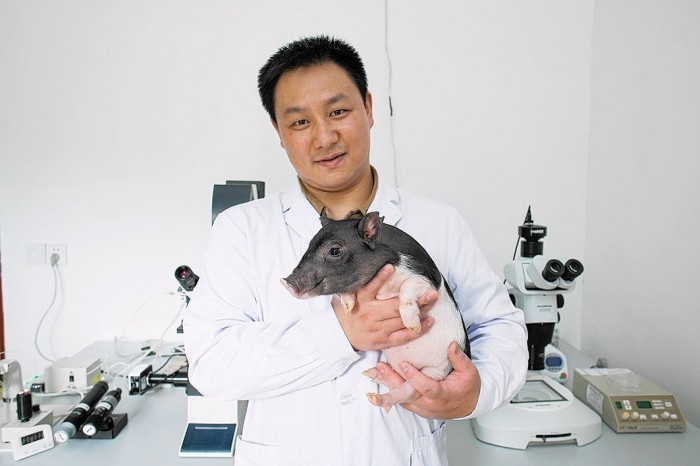

But BGI officials now say they won’t be marketing the pigs to consumers at all. “We have no plans to sell micropigs,” Yong Li, a key member of BGI’s animal science program, told MIT Technology Review.

Exactly why the plan got scrapped remains murky. But distracting press coverage, negative public sentiment in China around GMOs, and uncertainty over how China plans to regulate gene-modified animals all seem to have played a role.

Gene editing is a swift way to make surgical changes to animal embryos, often disabling genes or revising DNA to import into a breed traits that are found in other members of the same species. China in particular has raced ahead with the technology, generating long-haired goats and super-muscular dogs in its labs.

Some scientists have also hoped that sales of gene-edited animals, for food or other uses, wouldn’t be regulated. That is because the technology doesn’t involve introducing DNA from one species into another.

But regulators appear cautious. The U.S. FDA said in January that it would consider such animals GMOs, meaning potentially years of paperwork and delays for scientists working on creating hornless cattle and removing diseases from dogs. BGI’s Li says the government in China takes a similar view.

That means plans for designer pets, including dogs cured of genetic problems or pigs with designer fur, appear to be on hold. “This micropig project is still under review, and they are not for commercial sale,” said Siqi Gong, of BGI’s public relations department, adding that “no more detailed information will be disclosed.”

In May, BGI filed to carry out an initial public offering on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, with plans to raise about $250 million. It’s not the company’s first effort to go public. An attempt in 2016 failed after problems arose with the paperwork.

The company, originally named Beijing Genomics Institute, started out as a gene-sequencing specialist whose factory-like lab, and staff of thousands, made news by decoding the DNA of the giant panda and by soliciting DNA from geniuses to search for the genetic roots of IQ (see “Inside China’s Genome Factory”).

It also offered to cheaply sequence human genomes for academics around the globe.

Since then, the company has turned toward applied markets, like prenatal DNA testing, which accounts for half its revenue. BGI will be the first genomics company to go public in China, according to Nature, reflecting the country’s growing role in precision medicine.

To make the mini-pigs, BGI said, its scientists used a technology called TALENs to disable a gene for a growth-hormone receptor in pig embryos. The resulting pigs weighed only around 30 pounds, about as much as a cocker spaniel.

But gene-edited pets don’t appear anywhere in BGI’s 607-page stock offering document. That may be because genetically modified anything has become a sensitive issue in China, owing partly to years of food safety scandals and general distrust of regulatory oversight.

The government wants to change such perceptions, however. In June it tapped Tsinghua University to lead a survey of public attitudes toward GMO foods like transgenic soybeans as a means to determine how far and how fast they can be pushed, especially as the government urges companies to become global innovators in biotechnology.

While the tiny pigs might not be sold as pets, BGI is continuing its research on the animals at a 200-acre facility known as the Ark, located in the tropical coastal highlands east of Shenzhen. Li said the company is expanding the population of animals and testing breeding methods that could make for more robust specimens, including crossing them with wild pigs.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.