David Schwartz’s interest in the life of Enrico Fermi (1901–1954) was sparked by an essay about the legendary physicist that he found among his late father’s papers. Melvin Schwartz was a Nobel Prize–winning physicist himself, and the piece had been written by a friend who’d been a colleague of Fermi. Schwartz, PhD ’80, found the recollections fascinating and went looking for a biography. At that time, the most recent one available in English had been published in 1970. “I thought how wrong that is, for someone who is so important to be relatively unknown to contemporary students, academics, thinkers. A whole load of people who you would expect would know about Enrico Fermi don’t,” he says. “And so I set out to change that.”

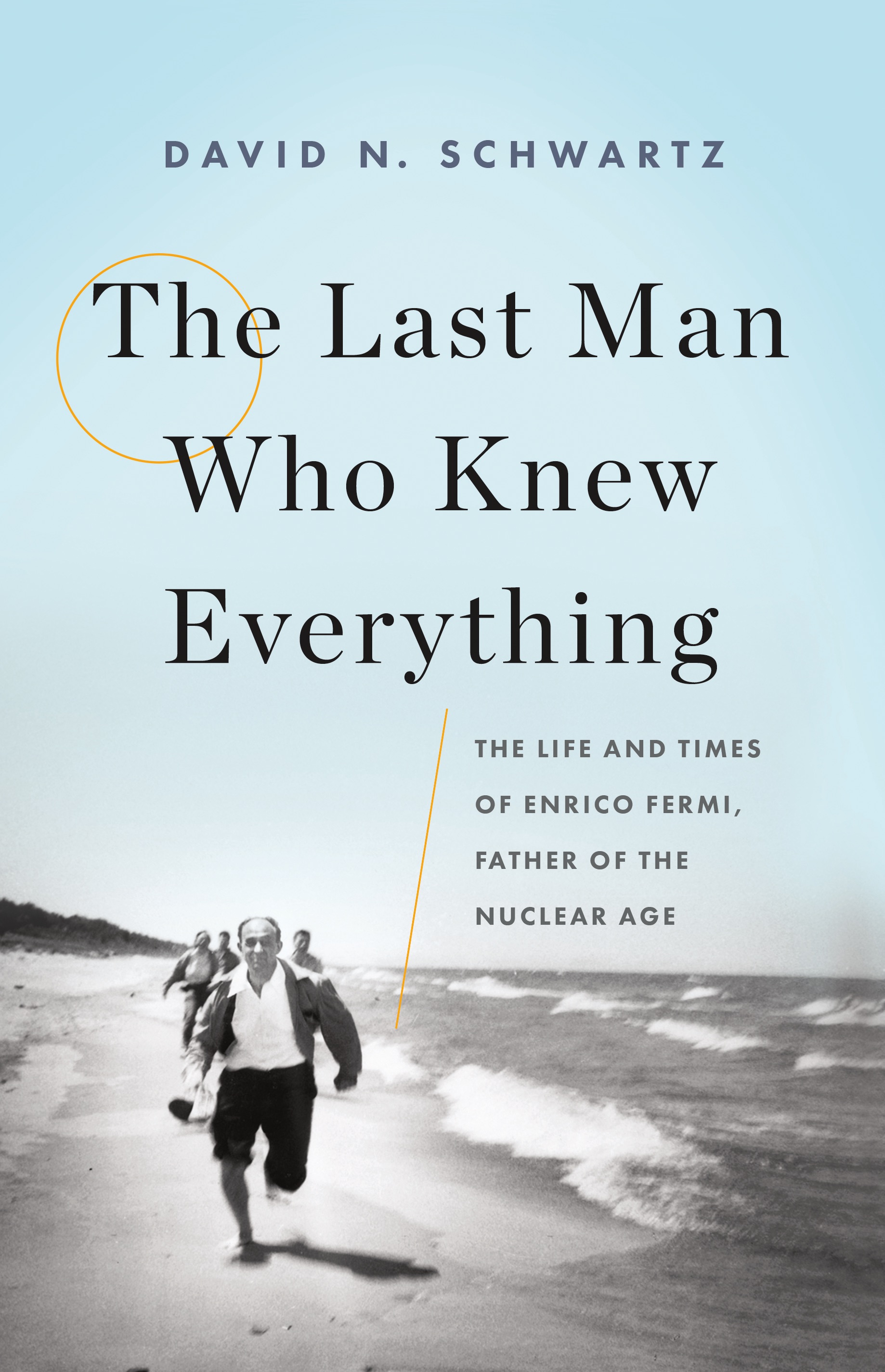

In The Last Man Who Knew Everything: The Life and Times of Enrico Fermi, Father of the Nuclear Age, Schwartz examines the private and professional life of the Italian-born scientist who has been called the “father of the atomic bomb.”

Fermi is known for his roles in the Manhattan Project and the world’s first nuclear reactor. (The book release coincides with the 75th anniversary of the first sustained nuclear chain reaction, at the University of Chicago.) Yet this is not a physics book, Schwartz writes, but “a book about a man who happened to be an extraordinary physicist and who also led an eventful, dramatic life.”

After he picked up his 1938 Nobel Prize in physics, for “work on the artificial radioactivity produced by neutrons and for nuclear reactions brought about by slow neutrons,” Fermi and his wife, Laura, who was Jewish, fled with their two children directly from Stockholm to New York. He joined the Columbia University faculty, and in 1939 he received funding from the US government—even though he was an Italian citizen and had been a member of the Fascist party—to conduct research that would lead to later work on the bomb.

Schwartz studied archives in Italy and Chicago, and he interviewed six of Fermi’s former American graduate students, then in their 80s and 90s. The picture that emerged, he says, was of a dedicated researcher who was equally passionate about teaching. “Fermi was an incredible inspiration to them,” says Schwartz. “For each of them, working with Fermi was a high point of their career … He was incredibly smart, very approachable, very generous, and a great teacher, someone who went out of his way, if you didn’t understand something, to go over it again and again until you did.”

Fermi’s scientific success took a toll on his personal life. His wife, a writer whose 1954 memoir is titled, tellingly, Atoms in the Family, “understood early on that she had married someone for whom physics was his first love,” says Schwartz. His children, however, found that harder to accept.

This is Schwartz’s first foray into biography; his previous two books focused on defense policy. In tackling the challenge, he says, he remembered the advice of his MIT thesis advisor, William Kaufmann: “Don’t worry so much about theory. Just write a cracking good story.”

Recent Books

From the MIT Community

The Future

By Nick Montfort, SM ’98, professor of digital media

MIT Press, 2018, $15.95

Leading Science and Technology: India Next?

By Varun Aggarwal, SM ’07, with a foreword by Desh Deshpande,’07 HM

Sage Publishing, 2018, $27.99

Modeling Human-System Interaction: Philosophical and Methodological Considerations, with Examples

By Thomas B. Sheridan, ScD ’59, professor emeritus of mechanical engineering and aero-astro

John Wiley & Sons, $110

The Telescope in the Ice: Inventing a New Astronomy at the South Pole

By Mark Bowen ’80, PhD ’85

St. Martin’s Press, 2017, $27.99

The Largest Art: A Measured Manifesto for a Plural Urbanism

By Brent D. Ryan, PhD ’02, associate professor of urban design and public policy and head of the City Design and Development Group

MIT Press, 2017, $44.95

Zero Waste in the Last Best Place: A Personal Account and How-To Guide on Landfill-Free Living

By Bradley Layton ’92

iUniverse, 2017, $13.99

The Inversion Factor: How to Thrive in the IoT Economy

By Linda Bernardi, Sanjay Sarma, professor of mechanical engineering and vice president for Open Learning, and Kenneth R. Traub ’84, SM ’86, PhD ’88

MIT Press, 2017, $29.95

Please submit titles of books and papers published in 2017 and 2018 to be considered for this column.

Contact MIT News

E-mail mitnews@technologyreview.com

Write MIT News, One Main Street, 13th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02142

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.