Win more social-media followers with this trick

In January, Turkish hackers mounted an unusual attack on Donald Trump by attempting to exploit his well-known obsession with social media. But instead of attacking the US president’s Twitter account directly, the hackers took control of several accounts that Trump follows. They then used these accounts to send him messages that included a malicious link.

Had the president clicked on this link, it would have revealed his Twitter password, giving the hackers control of his account. That would have allowed them to post their own messages, seemingly from the president of the United State, that would be perhaps even more damaging than the usual fare.

The attack raises important questions about the nature of malicious attacks on social networks. For example, the hackers could have tried a more subtle approach. Instead of attacking the accounts Trump follows, they could have simply interacted with them and attempted to influence them. The goal would have been to distort the Twitter filter through which Trump views the world.

This is by no means theoretical. Widespread evidence has emerged that malicious actors have attempted to influence thinking in the US and Europe by interacting with people on social media. The perpetrators created fake accounts to spread politically polarizing content, much of it fake itself. Just how influential this approach has been is the subject of significant public debate

Of course, the US has long done the same thing with its enemies. In 2014, the US State Department created a Twitter account called @ThinkAgain_DOS, which attempted to spread counter-propaganda against the Middle East terrorist organization Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). (The account is widely thought to have been ineffective.)

And that raises an important question. If somebody wants to influence an individual or set of individuals over Twitter, what is the best way to do it?

Today we get an answer thanks to the work of Fanyu Que at Boston College and Krishnan Rajagopalan and Tauhid Zaman, both at MIT. These guys have studied the factors that cause one person to follow another on Twitter—the so-called “follow-back problem.” With this information, they say, it is an order of magnitude easier to infiltrate that person’s social network than without it.

The team’s approach is relatively straightforward. To study how people follow others, they created six Twitter accounts that seemed, based on their content, to belong to Moroccan artists. The team then searched Twitter for other accounts that had posted tweets mentioning “Morocco” or “art.”

The “Moroccan artists” then interacted with these accounts—over 100 of them each—by retweeting one of their messages, following them, or replying to them. One control account did nothing other than tweet its own content. The team then measured the resulting conversion rate—the likelihood of other accounts to follow the artists.

It turns out that retweeting has a conversion rate of about 5 percent. In other words, 5 percent of the accounts the artists retweeted ended up following them. Following an account has a conversion rate of 14 percent.

But following and retweeting has a conversion rate of 30 percent. “The combined effect of these two interactions is greater than their separate individual effects,” say Que and co. They go on to show that if a high percentage of your followers also follow the target, that too increases the likelihood that the target will follow you.

All this immediately leads to a potential strategy for influencing individuals: build a following of the same people who follow the target, and then retweet and follow the target. That should significantly increase the probability the target will follow you.

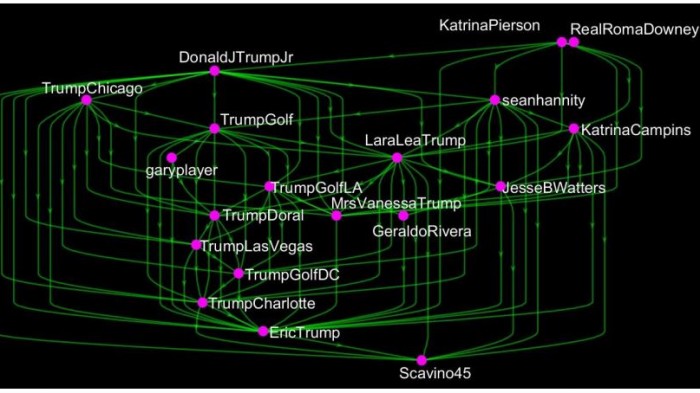

Que and co go on to study how this might work in practice by simulating the networks associated with influential individuals, such as Trump, Elon Musk, Emma Watson, and Justin Timberlake. They reconstruct the network of each these people’s friends and friends’ friends and then study how their optimal follow-back policy might spread through the network.

They begin by creating an agent’s account that attempts to influence each person in the simulated network. The outcome—whether this triggers a follow-back or not—is determined by the experimentally determined probabilities. And because the probability depends on who follows the agent, Que and co iterate the process some 10,000 times.

The results of these simulations are eye-opening “We find that our policies can increase the expected number of follows over simple policies by an order of magnitude,” say Que and co.

That’s impressive but also alarming. It means that not only are influential people targets for hackers, but so are the people they follow. Of course, these people may be influential in their own right and less easily targeted because they have so many followers or followees. So the optimal strategy is to target friends who are less influential.

Trump, however, is relatively well protected. He follows only 45 people, most of whom have significant numbers of followers themselves. That makes it harder for a malicious actor to create a fake account with a significant overlap of followers. So influencing the people Trump follows is hard. But for others it is much easier.

That has implications for hackers, but also for advertising and marketing campaigns. “Our work here could immediately be applied in advertising to improve targeted marketing campaigns,” say Que and co.

And that raises important ethical concerns, which they acknowledge. “Manipulating the flow of information to target audiences using artificial social media accounts raises many ethical concerns and can have tremendous impact over the targets’ understanding of world events and their subsequent actions,” they say. “In national security applications, it is important that these types of capabilities are used only under supervision of leadership in the intelligence or military communities.”

Quite! But how this kind of capability can be controlled is itself an awkward question, given the emerging problems associated with social media and the way malicious actors appear to work to undermine conventional opinion.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1804.02608 : Penetrating a Social Network: The Follow-Back Problem

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.