Spin control

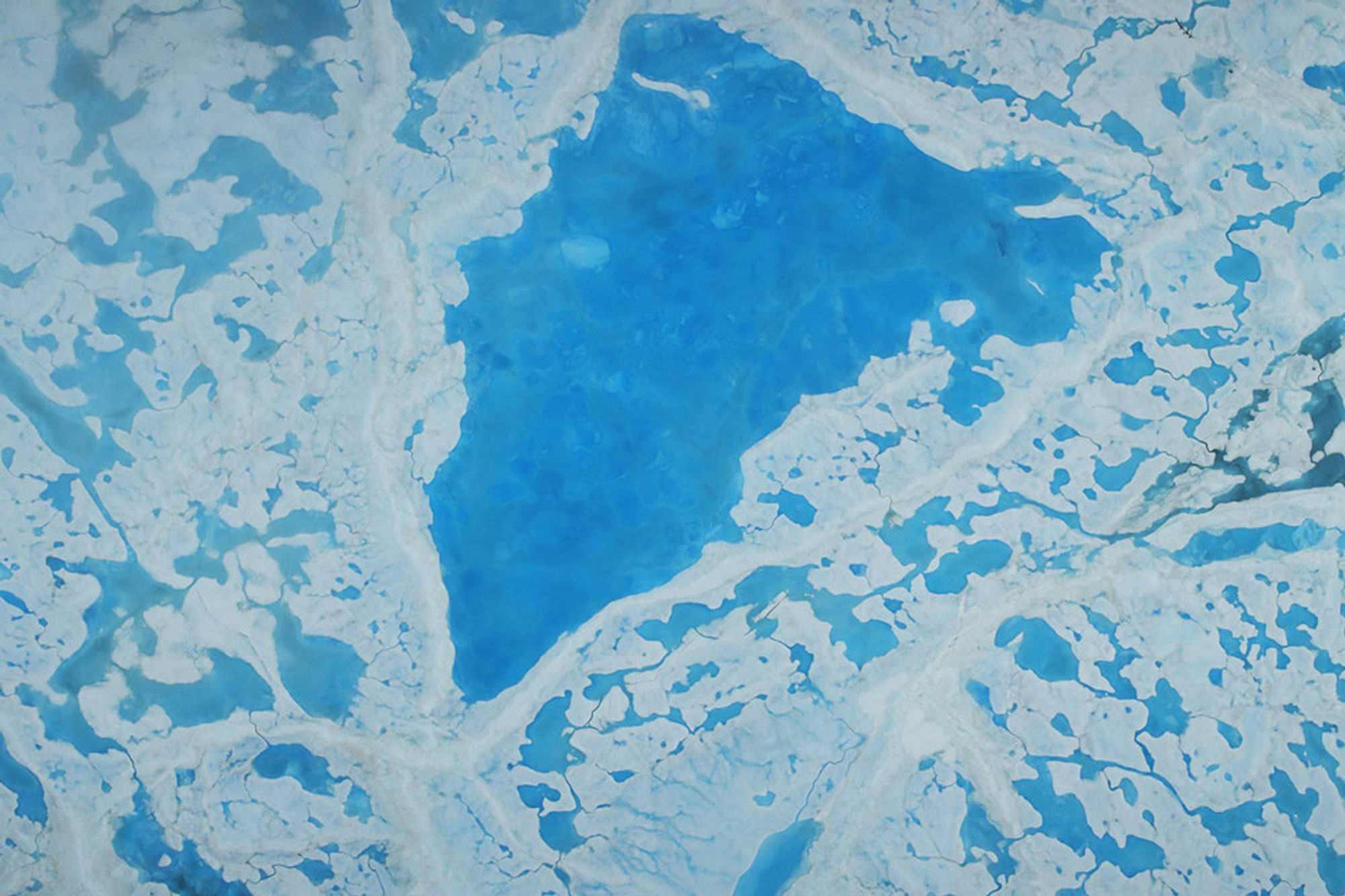

The Beaufort Gyre is an enormous, 600-mile-wide pool of swirling cold, fresh water in the Arctic Ocean, just north of Alaska and Canada. In the winter, this current is covered by a thick cap of ice. Each summer, as the ice melts away, the exposed gyre gathers up sea ice and river runoff, and draws it down to create a huge reservoir of frigid fresh water equal to the volume of all the Great Lakes combined.

Scientists at MIT have now identified a key mechanism, which they call the “ice-ocean governor,” that controls how fast the Beaufort Gyre spins and how much fresh water it stores. In a recent paper in Geophysical Research Letters, the researchers report that the Arctic’s ice cover essentially sets a speed limit on the gyre’s spin.

In the past two decades, as surface air temperatures have risen, the Arctic’s summer ice has progressively shrunk. The team has observed that with less ice available to control the Beaufort Gyre’s spin, the current has sped up in recent years, gathering up more sea ice and expanding in both volume and depth.

If Arctic temperatures continue to climb, the researchers predict, the mechanism governing the gyre’s spin will diminish. With no governor to limit its speed, the gyre is likely to transition into “a new regime” and eventually spill over like an overflowing bathtub, releasing huge volumes of cold, fresh water into the North Atlantic. That could affect the global climate and ocean circulation. “This changing ice cover in the Arctic is changing the system that is driving the Beaufort Gyre, and changing its stability and intensity,” says Gianluca Meneghello, an Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences research scientist.

As Arctic temperatures have risen in the last two decades, summertime ice has shrunk with each year, the speed of the Beaufort Gyre has increased, and its currents have become more variable and unpredictable, and they are only slightly slowed by the return of ice in the winter.

An increasingly unstable Beaufort Gyre could also disrupt the Arctic’s halocline—the underlying layer of ocean water that insulates ice at the surface from much deeper, warmer, and saltier water. If the halocline is weakened by a more unstable gyre, this could encourage warmer waters to rise up, further melting the Arctic ice.

“This is part of what we’re seeing in a warming world,” says oceanography professor John Marshall. “The Arctic is very vulnerable to climate change.” If this ice-ocean governor goes away, he says, we will end up with a very different Arctic ocean.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.