Industrial control systems are still vulnerable to malicious cyberattacks

Back in 1982, the CIA uncovered a plot by the Soviet Union to steal industrial software for controlling its rapidly expanding network of natural-gas pipelines. In response, the agency modified the software using malware designed to cripple the pipelines and then tricked the Soviets into stealing it.

This ruse turned out to be spectacularly successful. The Soviets installed the modified software—an industrial control system called SCADA—on a Siberian pipeline. After it operated normally for some months, the malware began closing safety valves, causing the pressure in the pipeline to rise beyond what the welds and joints could withstand. Eventually the pipeline exploded, causing “the most monumental non-nuclear explosion and fire ever seen from space,” according to the Washington Post, which reported the story in 2004.

This incident has gone down in history as the first example of a malware attack on an industrial control system. And it set the stage for a campaign of cyberattacks that shut down the phone system at the air traffic control center at the airport in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1997; disabled safety systems at the Davis-Besse nuclear power plant in 2003; and destroyed centrifuges at the secret Iranian nuclear enrichment facility in 2010—to name a just a few incidents.

Some of these attacks have generated huge publicity and raised awareness of how vulnerable industrial control systems are. So any company using industrial control software should be aware of the risks and protect it accordingly. But is that true?

Today we get an answer of sorts thanks to Marcin Nawrocki at the Free University of Berlin in Germany and colleagues, who have studied the rate at which industrial control systems send unprotected data across the internet. Their results provide a startling insight into these systems’ vulnerability.

Industrial control systems, such as SCADA and Modbus, were originally developed before the internet had spread widely. So they were designed to be simple and to work in a closed system unconnected to the outside world.

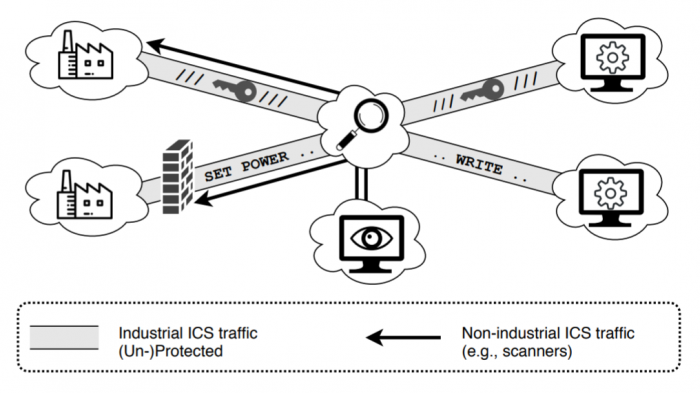

It later became possible to package the control signals in ordinary internet traffic so that industrial systems could be controlled remotely. However, this approach is entirely open. Anyone can scan internet traffic for these kinds of packets, look at where they are headed, and then send their own commands to take control.

And that is exactly how many of the earliest attacks occurred. Hackers could dial into industrial control systems using a telephone modem and either take control of or disable them.

So an entire industry has grown up to protect such systems. Because the software is so widespread, it cannot easily be rewritten. Instead, the main approach is to package the commands within another layer of software that is protected with conventional encryption, passwords, and so on. This prevents both unauthorized access to industrial control systems and eavesdropping on communication over the internet.

But does everyone use it? To find out, Nawrocki and co studied two databases of internet traffic. The first they collected from an internet exchange point (IXP) in 2017 and 2018. This is a point where internet service providers and content delivery networks exchange data. So it tends to be traffic from within the same country.

The second database was an archive of raw internet traffic between internet service providers (ISPs) in the US and Japan, which has been stored for research purposes. This data is, of course, transnational.

The first task for Nawrocki and co was to filter the data for the packets aimed at industrial control systems. They did this with a standard packet analyzer called Wireshark, which reveals unprotected packets.

But there is also another important filtering step. Because of the threats to industrial control systems, various projects have begun to monitor internet traffic—identifying and cataloguing industrial traffic, interrogating the hosts and sources where necessary, and setting up honeypots to attract malicious actors.

This activity by itself creates a significant amount of traffic related to industrial control networks. So Nawrocki and co had to filter the data sets to remove this as well.

What was left was interesting. They found over 330,000 unprotected packets related to industrial controls systems. In the international traffic between ISPs, this represented just 1.5% of the total industrial traffic.

But the situation is significantly worse at the local level, where 96% of the traffic consists of unprotected industrial commands. “The share (96%) of unprotected industrial [Industrial Control Systems] traffic at the IXP is alarming,” they say.

The team analyzed this unprotected traffic further using DNS records and whois data. They identified a range of companies sending unprotected traffic, including a solar energy consultancy, a building company, and a trade and transport company. These organizations are obviously at significant risk of malicious attack.

That’s interesting work revealing alarming levels of unprotected traffic that is putting industrial systems at risk.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1901.04411 : Uncovering Vulnerable Industrial Control Systems from the Internet Core

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

How Wi-Fi sensing became usable tech

After a decade of obscurity, the technology is being used to track people’s movements.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.