Rock lobster

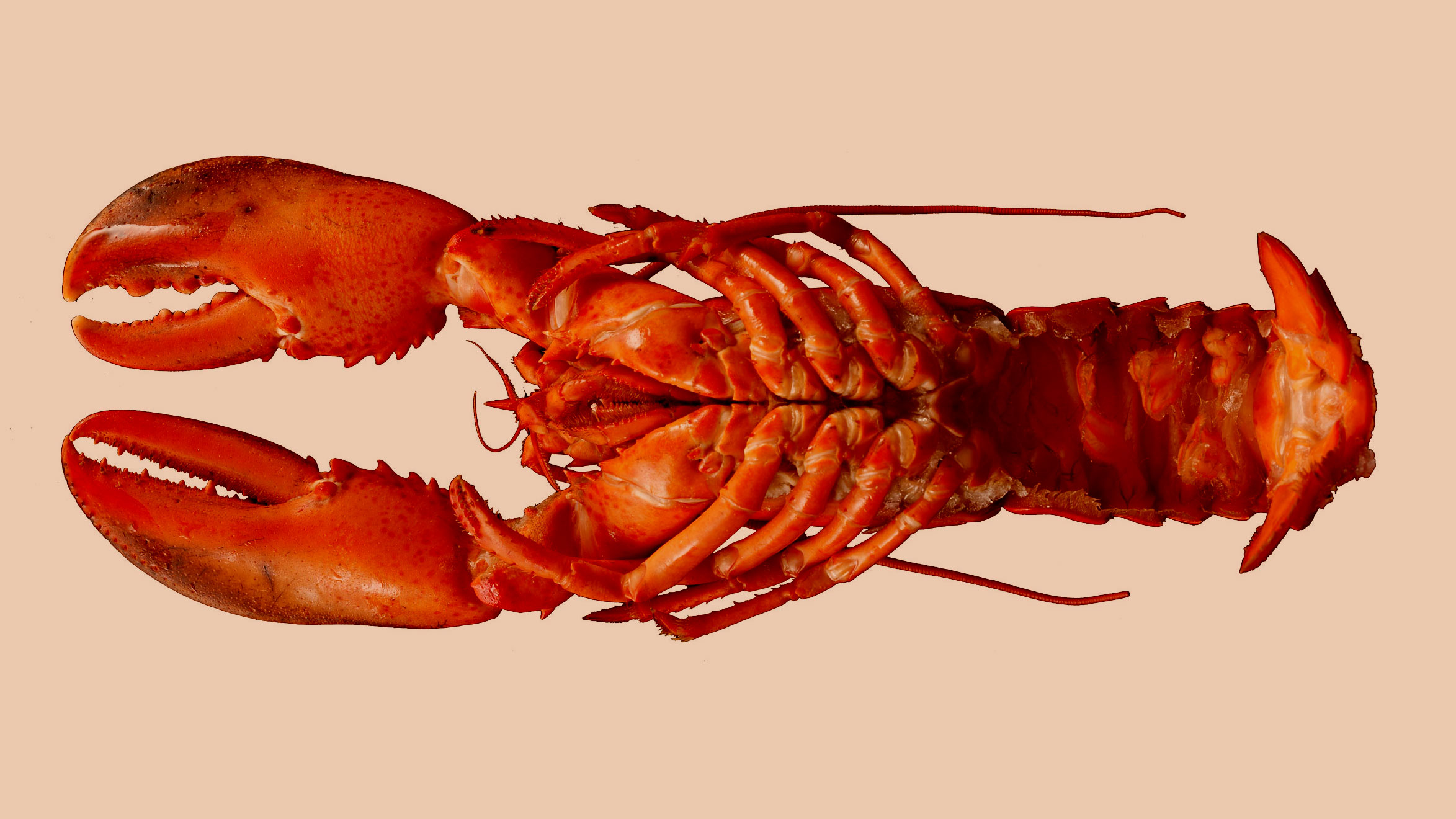

Flip a lobster on its back, and you’ll see that the underside of its tail is lined with a translucent membrane that appears more vulnerable than the armor-like carapace shielding the rest of the crustacean.

But MIT engineers have found that this soft membrane is surprisingly tough, with a plywood-like microscopic structure that prevents scrapes and cuts as the animal scuttles across the rocky seafloor.

The membrane is a natural hydrogel, composed of 90% water, so it’s flexible enough to allow the lobster to whip its tail back and forth. (Chitin, a fibrous material found in many shells and exoskeletons, makes up most of the rest.) But the membrane stiffens dramatically when stretched, making it difficult for a predator to chew through the tail or pull it apart.

The team discovered that the lobster membrane is the toughest of all natural hydrogels, including collagen, animal skins, and rubber. It’s also about as strong as industrial rubber composites, such as those used to make car tires, garden hoses, and conveyor belts.

The lobster’s tough yet stretchy membrane could inspire more flexible body armor, particularly for areas such as elbows and knees. Materials designed to mimic lobster membranes could also be useful in soft robotics and tissue engineering. And the results shed new light on the survival of one of nature’s most resilient creatures.

“We think this membrane structure could be a very important reason why lobsters have been living for more than 100 million years on Earth,” says Ming Guo, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering. “This fracture tolerance has really helped them in their evolution.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.