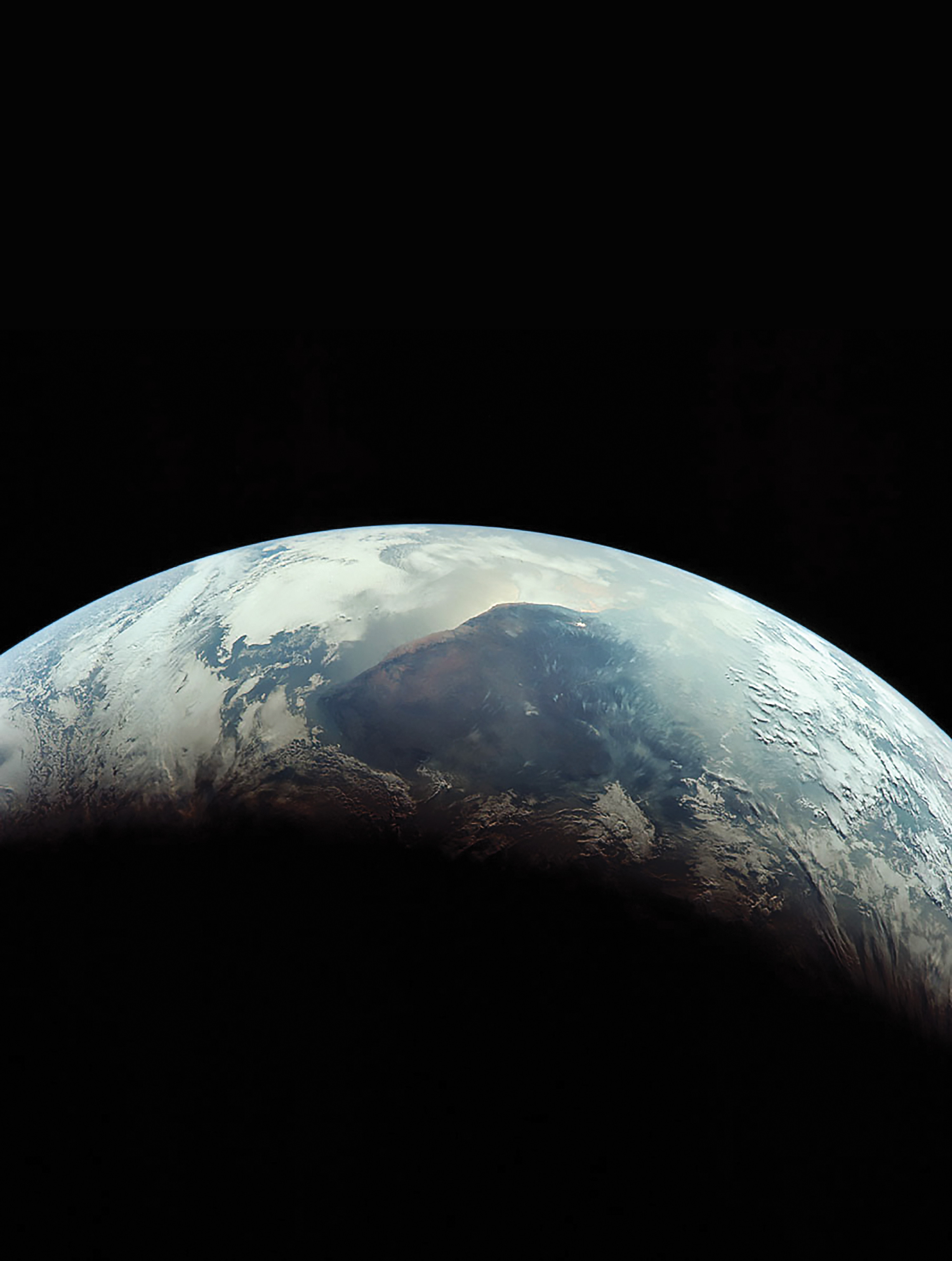

Where does space begin?

Like all geographical boundaries, the line between Earth and the heavens is indistinct. Just as the border between sea and land shifts with tides and waves, the atmosphere’s thickness varies from one day to the next.

There are physical and technological limits. If you travel up, the air grows thinner and the pressure drops. Were you to approach an altitude of 20 kilometers (12 miles) without pressurization, the blood in your lungs would boil. That’s about double the height at which commercial airliners fly, though the most capable airplanes have flown at nearly twice that altitude and balloons have reached over 50 kilometers.

In the end, as with borders on Earth, natural features might guide them, but political decisions define them. Nations claim sovereignty over their airspace—unwelcome flights above another country’s territory violate international law. But ever since Sputnik first overflew the United States and did not get shot down, it’s been widely accepted that sovereignty does not extend to space.

Going back to Soviet times, Russia (and others) have argued in the UN for a clear boundary: 100 km above mean sea level, 110 km—wherever you like, they said, so long as an unambiguous consensus is reached. The US has long blocked these efforts, as the US government believes that strategic ambiguity is desirable for things like high-altitude surveillance flights or hypersonic missiles.

Since the 1960s, the US Air Force has given astronaut wings to anyone who flies over 50 miles high (an awkward 80.4672 km, measured in metric units). America’s Federal Aviation Administration awards commercial astronaut wings to private pilots who exceed that altitude, which NASA also now recognizes. However, the World Air Sports Federation, which certifies world records for high-altitude flights, sets the boundary at 100 km (62.1371 miles). For companies like Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin that plan on taking tourists to the liminal zone for short times, how this line is drawn is, arguably, of critical economic importance: who wants to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to almost get to space?

Deep Dive

Space

How to safely watch and photograph the total solar eclipse

The solar eclipse this Monday, April 8, will be visible to millions. Here’s how to make the most of your experience.

How scientists are using quantum squeezing to push the limits of their sensors

Fuzziness may rule the quantum realm, but it can be manipulated to our advantage.

The race to fix space-weather forecasting before next big solar storm hits

Solar activity can knock satellites off track, raising the risk of collisions. Scientists are hoping improved atmospheric models will help.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.