The biggest loser in the presidential debates: Planet Earth

Climate change is becoming a bigger issue with left-leaning voters every day. Polls consistently show it leaping up their list of political concerns, propelled by a giant body of science that says our shift to clean energy isn't happening at anywhere near the scale or speed required to prevent catastrophic levels of warming.

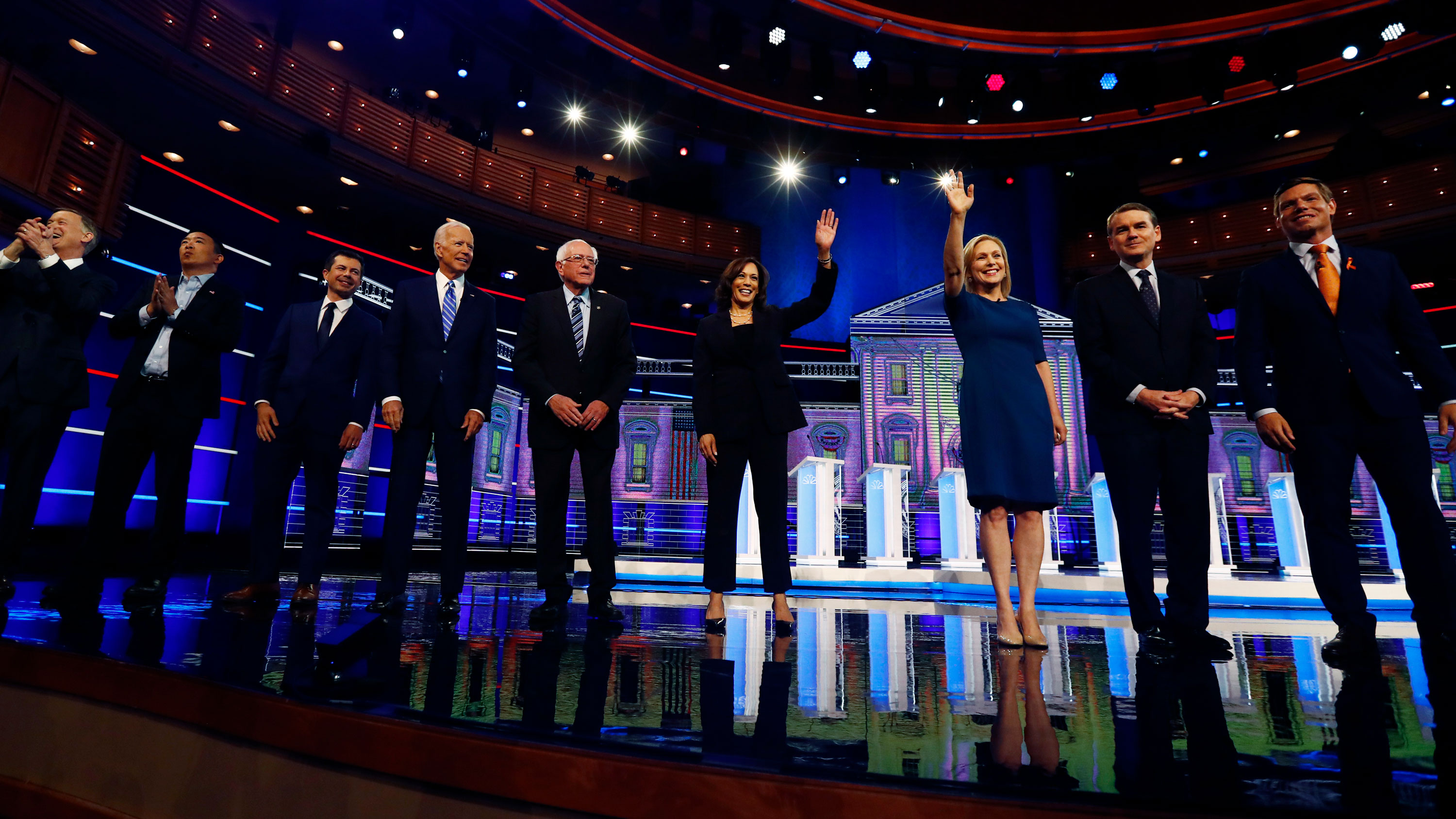

And yet, for two nights in a row, the issue—one that threatens to batter the US economy, its cities, and its citizens—was relegated to a handful of questions and a few minutes of answers during the two-hour Democratic presidential debates in Miami.

On Thursday night, the moderators spent about 12 minutes on the topic, deep into the second hour of political grandstanding. That was, at least, a little more than the seven minutes given to similar discussion during Wednesday night’s first debate. And this lack of attention was compounded by rules that forced the candidates to complete their responses inside 60 seconds, ensuring that few got into any great depth and nuance on a complex topic.

(Here are the tech-focused questions we would have posed: “Seven climate questions we’d ask the Democratic presidential candidates tonight.”)

Senator Kamala Harris of California consistently delivered the sharpest sound bites throughout Thursday’s second debate, and environmental concerns were no exception. She referred to a climate crisis that represents an “existential threat to us as the species,” and took a shot at President Trump’s embrace of “science fiction over science fact.”

She stressed her support for the Green New Deal, and said she would recommit the US to the Paris agreement on her first day as president. But then she made an awkward pivot into critiques of Trump and his handling of North Korea.

A few of the other candidates offered more detailed policy proposals.

Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, stressed the importance of taking more aggressive actions to adapt to dangers including sea-level rise in Florida and flooding in the Midwest. He also called for a carbon tax and dividend that delivers rebates to citizens, and suggested that farmers could help capture and store carbon dioxide in soil. (The science is still mixed on that, however, as we recently reported: “Carbon farming is the hot (and overhyped) tool to fight climate change.”)

Former vice president Joe Biden hit some of the bullet points from his climate plan, including creating 500,000 electric-vehicle charging stations and investing $400 billion into research and development. (He actually said “million,” but we’ll assume that was a slip of the tongue rather than a dramatic scaling down of his earlier proposal.) Biden also said he’d bring the US back into the Paris agreement on climate change, but stressed the importance of pushing the rest of the world to take more aggressive action.

“We have to have someone who knows how to corral the rest of the world, bring them together, and get something done like we did in my administration,” he said.

The previous night, Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts did an artful job of connecting climate to simmering public concerns around big business and economic inequality. The economy, she declared in her opening statement “is doing great for giant oil companies that want to drill everywhere, just not for the rest of us who are watching climate change bear down upon us.”

But others flubbed their chances to seize the climate moment.

When asked a roundabout question Wednesday on how to fund climate mitigation, Representative Tim Ryan of Ohio said only that there are a “variety of different ways” to do so. John Hickenlooper, the former governor of Colorado, twice suggested that the Green New Deal represented a slide into socialism, while stressing that Democrats should work with the oil and gas industry and not “demonize every business.”

Four of 10 candidates on Wednesday cited climate among the top threats the US faces, but only two of 10 on Thursday said clearly that it would be the first policy priority in their administration. Those included Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado and Hickenlooper. Buttigieg and entrepreneur Andrew Yang both said fixing others things would make tackling climate easier, specifically "fix[ing] our democracy" and putting in place universal basic income, respectively.

Of all the candidates on display, Jay Inslee, the governor of Washington, has made climate the most central part of his campaign. And he came closest to laying down a coherent argument for why it should matter to voters, arguing that it should be the nation’s and every candidate’s top priority.

“We are the first generation to feel the sting of climate change, and we are the last that can do something [about] it,” he said, according to the Washington Post’s transcript. “Our towns are burning. Our fields are flooding. Miami is inundated.”

He’s right. It is a crisis in every sense except our response to it.

There are, of course, other important issues in the US, including the economy, inequality, civil rights, education, infrastructure, immigration, health care, and safety. But climate change undermines our ability to grapple with all of them, as rising temperatures and extreme weather inflict devastating economic costs and threaten lives.

In the last three years, the US has faced its most expensive hurricane season in history, California’s most destructive and deadliest fires ever, and record flooding in the Midwest. At the same time, glaciers are melting, permafrost is thawing, and oceans are warming, all at faster rates than scientists predicted.

And it’s all set to get much, much worse. The National Climate Assessment released late last year found that economic damages from climate change could add up to $700 billion in the US by 2090 (see “Death will be one of the highest economic costs of climate change”).

The presidential debates represented a rare opportunity for the contenders for the country’s highest office to speak directly to the public. Alongside voting, they are among the few moments when millions of citizens collectively engage in the political process. More than 15 million people watched the first debate on Wednesday night alone.

It’s a brief opportunity to declare our highest national political priorities to the audience that needs to hear it.

“We have a lot of research that shows the public takes cues from elites and politicians,” says Leah Stokes, an assistant professor focused on energy and environmental politics at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “So if a politician talks about climate change in compelling ways and explains to the public that it’s happening now, damaging the American economy, and putting lives at risk, that helps everyday citizens understand the scale and urgency of the problem.”

On that basis, dedicating about 20 minutes to climate change across four hours of live broadcast debates is a tragic waste of an opportunity, and a dereliction of duty by the moderators, the Democratic Party—and at least some of the candidates themselves.

This story was updated to clarify which candidates cited climate change among their highest political priorities.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Harvard has halted its long-planned atmospheric geoengineering experiment

The decision follows years of controversy and the departure of one of the program’s key researchers.

Why hydrogen is losing the race to power cleaner cars

Batteries are dominating zero-emissions vehicles, and the fuel has better uses elsewhere.

Decarbonizing production of energy is a quick win

Clean technologies, including carbon management platforms, enable the global energy industry to play a crucial role in the transition to net zero.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.